|

Analysis of Accountability: Corporate

Structure and Inter-corporate Responsibilities

The concept of accountability applies when a

person or organization is responsible to another. It is an abstract notion that

can represent

many specific issues, including organization structures, contracts, and

employment.

This analysis begins by introducing the important pattern of Party

(Section 1) - the super-type of person and organization.

The organization structure problem is then used to show the development of the

accountability model. Simple organization structures can be

modeled with Organization Hierarchies (Section 2). When many

hierarchies develop the model becomes too complex, and the

Organization Structure (Section 3) pattern is required. The

combination of the party and organization structure patterns produces Accountability (Section 4). Accountabilities can handle many

relationships between parties: organization structures, patient consent,

contracts for services, employment, and registration with professional bodies.

When accountabilities are used it is valuable to describe what kinds of

accountabilities can be formed and the rules that constrain these

accountabilities.

These rules can be described by instances of types at the Accountability

Knowledge Level (Section 5). This level includes the party type,

which allows parties to be classified and sub-typed with Party Type

Generalizations (Section 6) without changing the model.

Hierarchic Accountability (Section 7) represents those interparty

relationships that do require a strict hierarchy. In this way accountabilities

can be

used for both hierarchic and more complex networks of relationships.

Accountabilities define responsibilities for parties. These responsibilities can

be defined through Operating Scopes (Section 8).

Operating scopes are the clauses of the accountability's contract, rather like

line items on an ongoing order. As these responsibilities accumulate

it can be useful to attach them to a Post (Section 9) rather than

to the person who occupies it.

This analysis is based on many projects: Accountabilities are a common theme.

Original ideas developed with a customer service project

for a utility and an accounting project for a telephone company. The

accountability model was first introduced in the Cosmos project for the

UK National Health Service.

Key Concepts: Party, Accountability

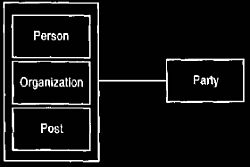

1. Party

Take a look through your address book, and you will see a lot of addresses,

telephone numbers, the odd e-mail address... all linked to something.

Often that something is a person, but once in a while a company shows up. We

call Town Taxi frequently, but there's no particular person we want

to speak to there - We just want to get a cab. A first attempt at modeling the

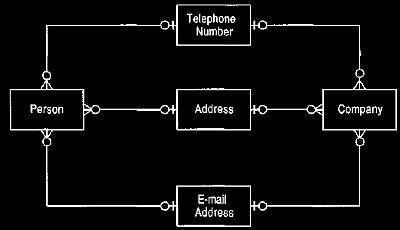

address book might be Figure 1, but it has a duplication that is painful to an

eye.

Instinctively we look for a generalization of person and company. This type is a

classic case of an unnamed concept - one that everybody knows and uses

but nobody has a name for. We have seen it on countless data models on various

names: person/organization, player, legal entity, and so on.

Figure 1 Initial model of an address book.

This model shows the similar responsibilities of person and organization.

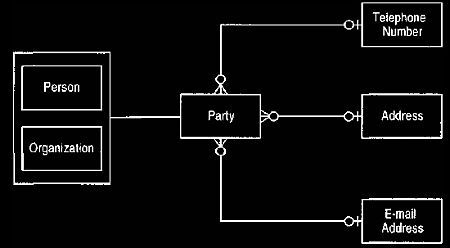

The term we prefer is party. In Figure 2 we define a party as the super-type of a

person or organization. This allows us to have addresses and

phone numbers for departments within companies, or even informal teams.

Figure 2 Figure 1 generalized using party.

Party should be used in many situations where person or organization is used.

It is surprising how many things relate to party rather than to person or

organization. You receive and send letters to both people and organizational

units; we make payments to people and organizations; both organizations and

people carry out actions, have bank accounts, file taxes.

These examples are enough to make the abstraction worthwhile.

Example: In the UK National Health Service, the following would be

parties: Dr. John Doe, the renal unit team at St. Mary's Hospital,

St. Mary's Hospital, Parkside District Health Authority, and the Royal College

of Physicians.

2. Organization Hierarchies

Let us consider a generic multinational: Aroma Coffee Makers, Inc. (ACM). It has

operating units, which are divided into regions,

which are divided into divisions which are divided into sales offices. We can

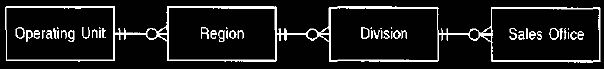

model this simple structure using Figure 3.

Figure 3. Organization structure with explicit levels.

Such a structure is inflexible and not reusable.

This is not a model that we would feel content with, however. If the organization

changes, say regions are taken out to provide a flatter structure, then

we must alter the model. Figure 4 provides a simpler model—one that is easier to

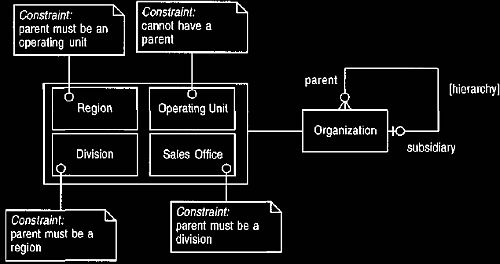

change. The danger with the recursive relationship shown in Figure 4

is that it allows a division to be part of a sales office. We can deal with this

by defining sub-types to correspond with the levels and by putting constraints

on these sub-types. Should the organizational hierarchy change, we would alter

these sub-types and rules. Usually it is easier to change a rule than to change the model structure, so we prefer Figure 4 over Figure 3.

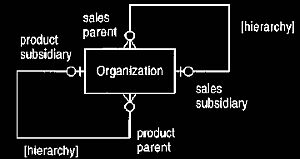

Figure 4 Organization super-type with hierarchic relationship.

The hierarchic association provides the most flexibility. Constraints due to

levels have to be added as rules on the sub-types.

The hierarchic structure provides a certain amount of generality but has some

limitations, including the fact that it only supports a single organizational

hierarchy. Assume that ACM attaches service teams for its major lines of coffee

makers to its sales offices. These teams have a dual reporting structure.

They report to the sales team as well as the service departments for each

product family, which in turn report to product type support units.

Thus the service team for the 2176 high-volume cappuccino maker in Boston (50

cappuccinos a minute) reports to the Boston sales office but also to the

2170 family service center, which reports to the high-volume Italian coffee

division, which reports to the high-volume coffee products service division,

which reports to coffee products service division. (I'm not making this up

entirely!) Faced with this situation we can add a second hierarchy, as shown in

Figure 5.

(More rules would be required, similar to those in Figure 4, but we will leave

the addition of those as an exercise for the reader.) As it stands this approach

works well,

but as more hierarchies appear the structure will become unwieldy.

Figure 5 Two organizational hierarchies.

Sub-types of the organization are not shown. If there are many hierarchies,

this will soon get out of hand.

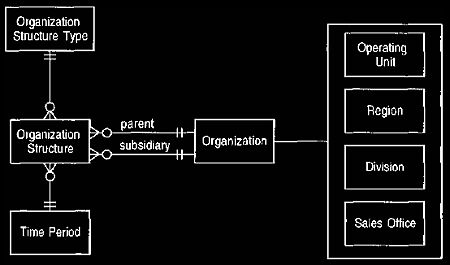

3. Organization Structure

If it looks like the model will have several

hierarchies, we can use a typed relationship, as shown in Figure 6. We turn the

hierarchic associations into a type and differentiate the hierarchies by using varied instances of the

organization structure type. This would handle the above scenario with two

instances

of the organization structure type: sales organization and service organization.

Additional hierarchies could be added merely by adding more organization

structure types. Again, this abstraction gives us more flexibility for a modest

increase in complexity. For just two hierarchies it would not be worth the

effort,

but for several it would be. Note also that the organization structure has a

time period; this allows us to record changes in the organization structure over

time.

Note further that we have not modeled the organization structure type as an

attribute—a very important factor with type attributes, as we will see later.

Example: The service team for the 2176 high-volume cappuccino maker in Boston

reports to the Boston sales office. We would model this as an organization

structure whose parent is the Boston sales office, subsidiary is the Boston 2176

service team, and organization structure type is line management.

Example: The service team for the 2176 high-volume cappuccino maker in Boston

also reports to the 2170 family service center in the product support structure.

We would model this as a separate organization structure whose parent is the

2170 family service center, subsidiary is the Boston 2176 service team, and

organization structure type is product support.

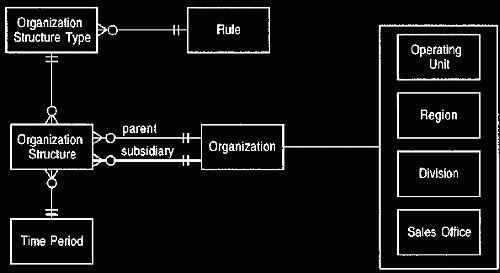

Simplifying the object structure puts more emphasis on the rules. The rules are

of the form, "If we have an organization structure whose type is sales

organization and whose child is a division, then the parent must be a region."

Note that the rules are expressed by referring to properties of the organization

structure, which implies that the rules should be on the organization structure.

However, this means that extending the system by adding a new organization

structure type would require changing the rules in the organization structure.

Furthermore, the rules would get very unwieldy as the number of organization

structure types increases.

Figure 6 Using a typed relationship.

Each relationship between organizations is defined by an organization

structure type. It is better than explicit associations

if there are many relationships.

The rules can be placed instead on the organization structure type, as shown in

Figure 7. All the rules for a particular organization structure type are held in

one place, and it is easy to add new organization structure types.

Figure 7 does not work well, however, if we change the organization structure

types rarely but add new sub-types of organization frequently. In that

case each addition of a sub-type of organization would cause rule changes. It is

better to place the rules on the sub-types of the organization.

The general point here is to minimize the model changes that occur. Thus we

should place the rules in the most volatile area in such a way that need not

touch other parts of the model.

Modeling Principle: Design a model so that the most frequent modification

of the model causes changes to the least number of types.

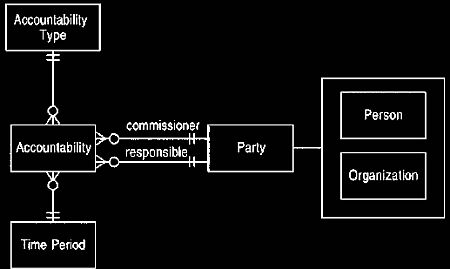

4. Accountability

Essentially Figure 7 shows one organization having a relationship with another

for a period of time according to a defined rule. Whenever any statement

is made about organizations, it is always worth considering whether the same

statement can also apply to people. In this case we ask, "Can people have

relationships to organizations or other people for a period of time according to

a defined rule?" This is certainly true, and thus we can, and should, abstract

Figure 7 to apply to a party. As we do this we name the new abstraction an

accountability, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 7 Adding a rule to Figure 6.

The rule enforces constraints such as sales offices reporting to divisions.

Figure 8 Accountability.

Using a party allows accountability to cover a wide range of interparty

responsibilities, including management, employment, and contracts.

Example: John Smith works for ACM. This can be modeled by an

accountability whose commissioner is ACM, responsible party is

John Smith, and accountability type is employment.

Example: John Smith is the manager of the Boston 2176 service team. This

can be modeled as an accountability whose type is manager,

with John Smith responsible to the Boston 2176 service team.

Example: Mark Jones is a member of the Royal College of Physicians. This

can be modeled as an accountability whose type is

professional registration, with Mark Jones responsible to the Royal College of

Physicians.

Example: John Smith gives his consent to Mark Jones to perform an

endoscopy. This can be modeled as an accountability whose type is

patient consent, with Mark Jones responsible to John Smith.

Example: St. Mary's Hospital has a contract with Parkside District Health

Authority to perform endoscopies in 2006/2007. This can be

modeled as an accountability whose type is endoscopy services, with St. Mary's

Hospital responsible to Parkside. The time period on the

accountability would be January 1, 2006, to December 31, 2007. A sub-type of

accountability could provide additional information, such as which

operations were covered and how many should be performed during the contract's

duration.

Modeling Principle: Whenever defining features for a type that has a

super-type, consider whether placing the features on the super-type makes sense.

As the examples indicate, abstracting from organization structure to

accountability introduces a wide range of additional situations that can be

captured by the model. The complexity of the model has not increased, however.

The basic model has the same structure as Figure 7;

the only change is that of using party instead of organization.

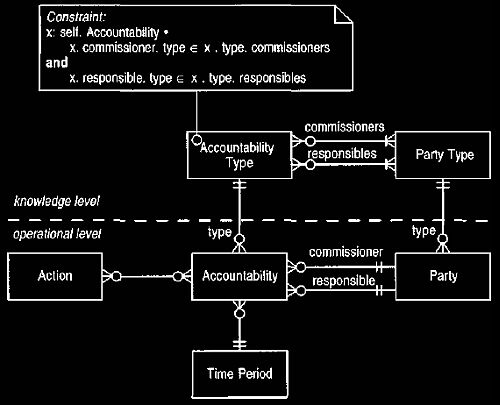

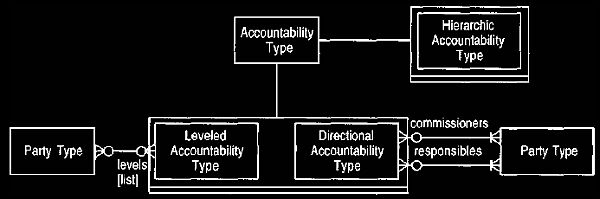

5. Accountability Knowledge Level

Complexity has been introduced, however, in that there are many more

accountability types than there would be organization structure types.

The rules for defining accountability types would thus become more complex.

This complexity can be managed by introducing a knowledge level. Using a

knowledge level splits the model into two sections: the operational

and knowledge levels. The operational level consists of accountability, party,

and their interrelationships. The knowledge level consists of

accountability type, party type, and their interrelationships, as shown in

Figure 9.

At the operational level the model records the day to day events of the domain.

At the knowledge level the model records the general rules that

govern this structure. Instances in the knowledge level govern the configuration

of instances in the operational level. In this example

instances of accountability (links between actual parties) are constrained by

the links between accountability type and party type.

Figure 9 Knowledge and operational levels of accountability.

The knowledge level objects define the legal configurations of operational

level objects.

Accountabilities can only be created between parties according to corresponding

accountability types and party types.

Example: Regions are subdivided into divisions. This is handled by an

accountability type of regional structure whose commissioners

are regions and responsibles are divisions.

Example: Patient consent is defined as an accountability type whose

commissioners are patients and responsibles are doctors.

Note how mapping to the party type replaces sub-typing of the party. This is an

example: of what Odell refers to as a power type,

which occurs when a mapping defines sub-types. The party type is closely linked

to the sub-types of party in that the sub-type region

must have its type as the party type region. Conceptually you can consider the

instance of the party type to be the same object

as the sub-type of party, although this cannot be directly implemented in

mainstream programming languages.

The party type is then a power type of party. Often we need only one of either

the mapping or the sub-typing.

However, if the sub-types have specific behavior and the power type has its own

features, then both sub-types and mapping to the

power type are needed.This reflection between the knowledge and operational

levels is similar but not identical, in that the parent and

subsidiary mappings are multivalued at the knowledge level but single-valued at

the operational level. This is because the operational level

records the actual party for the accountability, while the knowledge level

records the permissible party types for the accountability type.

This use of a multivalued knowledge mapping to show permissible types for a

single-valued operational mapping is a common pattern.

Knowledge and operational levels are a common feature of models, although the

difference between the levels is often not made explicitly.

We make the divisions explicit because we find this helps to clarify our thinking

when modeling. We give lots of examples of operational

and knowledge levels, particularly in

Analysis of Clinical Observations.

Modeling Principle: Explicitly divide a model into operational and

knowledge levels.

A lot of data modelers use the term meta-model to describe the knowledge level.

We are not entirely comfortable with this terminology.

Meta-model can also define the modeling technique. Thus a meta-model includes

concepts such as type, association, sub-typing, and

operation (such as the meta-models of Rational Software's Unified Method). The

knowledge level does not really fall into that category

because it does not describe the notation for the operational level. We thus only

use the term meta-model to describe a model that describes

the language (semantics of notation) for a model.

Accountability represents some pretty heady abstraction and as in any climb we

should stop and take stock before altitude sickness sets in.

Although we have a very simple structure in the object model, a lot of knowledge

is buried in the instances of the knowledge level.

Thus to make this work it is not enough to implement the object model; the

knowledge level must also be instantiated.

Instantiating the knowledge level is effectively configuring the system, which

is a constrained, and thus simpler, form of programming.

It is still programming, however, so you should consider how you are going to

test it.

Rich knowledge levels also affect communication between systems. If two systems

are to communicate, they must not only share the

object model but also have identical knowledge objects (or at least some

equivalence between knowledge levels, as discussed in

In the end it comes down to the question, If the number of accountability types

is large, is it easier to use the structure of Figure 9 or to

extend Figure 5 with one association for each accountability type? The

complexity of the problem cannot be avoided; we can only ask ourselves

which is the simpler model, taking both type structure and knowledge objects

into account.

We need to be careful, as with any typed relationship, that this does not become

a catch-all for every relationship between two parties.

For example, biological parent would not fit as an instance of an accountability

type because neither party is responsible to the other,

nor is there an inherent time period; legal guardian would fit, however.

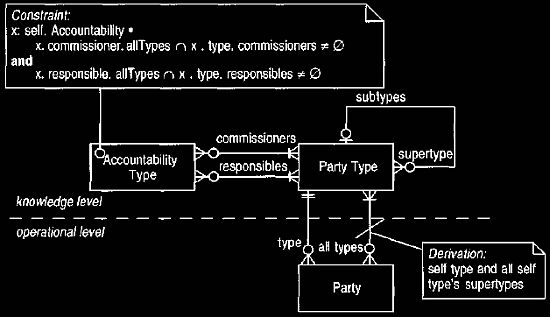

6. Party Type Generalizations

The model as it stands is quite powerful, but some useful variations will add

even more flexibility. These variations are useful with any model

that uses a knowledge/operational split.

Consider a general practitioner (GP), Dr. Edwards. Using the model shown in

Figure 9, we can consider him to be a GP or a doctor but not both.

Any accountability types that are defined on doctor that would apply also to GP

would have to be copied over. We can use various techniques

to alleviate this problem. One approach is to allow party types to have sub- and

super-types relationships, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10 Allowing party types to have sub-and super-types.

Adding generalization to party types makes it easier to define the knowledge

level.

This essentially introduces generalization to party types in a similar way that

generalization works on types. Generalizations cause a change

in the constraint on accountability type, so that both the party's type (from

the type mapping) and the super-types (from the all types mapping)

are taken into account.

Figure 10 provides a single inheritance hierarchy on party type. Multiple

inheritance can be supported by allowing the super-type mapping to be

multivalued. In addition, Figure 10 only supports single classification. This

means that if Dr. Edwards is both a GP and a pediatrician, we can record

that only by creating a special GP/pediatrician party type, with both GP and

pediatrician as super-types. Multiple classification allows party to be

given multiple party types outside of the generalization structure of party

type. This can be done by allowing the type mapping on party to be multivalued.

Much of the discussion about the interrelationships between the knowledge level

and operational level is similar to the relationships between

object and type in a modeling meta-model.

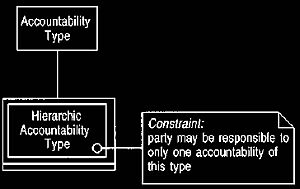

7. Hierarchic Accountability

The flexible structure that accountabilities provide requires more effort to

enforce the constraints of some accountability types.

For example, the organization structure shown in Figure 3 defines a strict

series of levels: operating units are divided into regions,

that are divided into divisions that are divided into sales offices. It is

possible to define an accountability type of regional structure, but

how can we enforce the strict rules of Figure 3?

The first issue is that Figure 3 describes a hierarchic structure. The

accountability models do not have a rule to enforce such a hierarchy.

This can be addressed by providing a sub-type of accountability type with an

additional constraint, as shown in Figure 11. This constraint

acts with the usual constraint on accountability types to enforce the hierarchic

nature of the operational level structure. A similar accountability

type sub-type can be used to enforce a directed acyclic graph structure.

Using Figure 11, we can support the case shown in Figure 3 by a series of

accountability types. An accountability type regional structure level

would have regions responsible to operating units, regional structure

level 2 would have divisions responsible to regions, and so on.

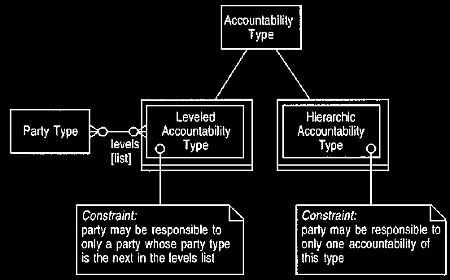

This approach works but would be somewhat clumsy. An alternative is to use a

leveled accountability type, as shown in Figure 12.

In this case there would only be a single regional structure accountability

type. The levels mapping would map to the list of party

types—operating unit, region, division, and sales office. This model makes it

easier to add new leveled accountability types and to modify the

levels in those structures that need it. The hierarchic accountability type

captures the responsibility of the parties forming a hierarchy, the

leveled accountability type captures the responsibility of a fixed sequence of

party types.

Figure 11. Hierarchic accountability type.

The added constraint means that the parties linked by accountabilities of

this type must form a hierarchy.

The regional structure accountability type would be both leveled and hierarchic.

Figure 12. Leveled accountability type.

Leveled accountabilities supports fixed levels such as sales office,

division, region.

The constraints applied on the sub-types act with the constraint defined on

accountability type, following the principles of design by contract.

In the case of the leveled accountability type, the constraint subsumes that of

the super-type, and indeed makes the commissioners and

responsibles mappings superfluous. This thinking leads to a model along the

lines of Figure 13. It is important to note that Figure 12 is not incorrect.

Leveled accountability type is a perfectly good sub-type of accountability type

because the constraint on accountability type will still hold for

leveled accountability type. The commissioners and responsibles mappings will

also continue to hold, although they would be derived from the

levels mapping. We would be inclined to stick with Figure 12. The leveled

accountability type is not always needed, and can easily

be added without violating the model. Figure 12 also has the advantage of making

the knowledge/operational relationship more explicit.

Figure 13. Rebalancing the sub-types of accountability type. A better way of

organizing the accountability type hierarchy.

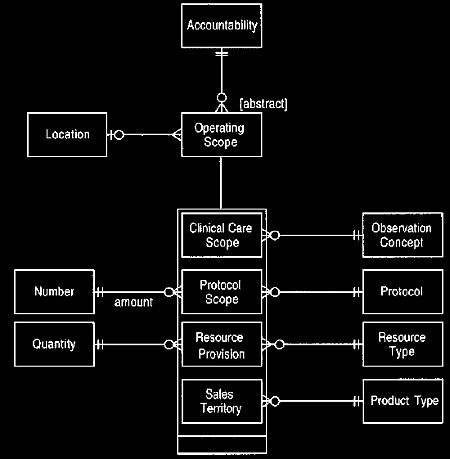

Accountability, as it stands, provides a valuable way of describing how parties

relate to each other. The type of accountability describes

what kind of relationship they have. There are usually other details, however,

that describe more of the meaning of accountability.

Consider a doctor who might be employed as a liver surgeon to carry out 20 liver

transplants for southeast London in 2002. A diabetic

care team at a hospital might be asked to care for insulin-dependent diabetes

patients in western Massachusetts for the Red Shield HMO

(Health Management Organization).

Such details are the operating scopes of accountability, as shown in Figure 14.

Each operating scope defines some part of consequences

of accountability on the responsible party. It is difficult to enumerate the

attributes of an operating scope in the abstract. Thus we see that

accountability has a number of operating scopes, each of which is some sub-type

that describes the actual characteristics.

Figure 14. Operating scope.

Operating scopes define the responsibilities that are taken on when an

accountability is created. They can be used for job descriptions.

Example: A liver surgeon who is responsible for 20 liver transplants a

year in southeast London has a protocol scope on

employment accountability with amount of 20, protocol of liver transplant, and

location of southeast London.

Example: A diabetic care team has accountability with Red Shield. This

accountability would have a clinical care scope whose

observation concept is insulin-dependent diabetes and location is western

Massachusetts.

Example: ACM has a contract with Indonesian Coffee Exporters (ICE) for

3000 tons of Java and 2000 tons of Sumatra over

the course of a year. This is described by accountability between ACM and ICE

with a year's time period and two resource provisions:

3000 tons/ year of Java and 2000 tons/year of Sumatra.

Example: John Smith sells the 1100 and 2170 families of high-volume

coffee maker for ACM. He sells both the 1100 and 2170 in

New England and sells the 2170 in New York. He has employment accountability to

ACM with sales territories for 1100 in New England,

2170 in New England, and 2170 in New York.

When using operating scopes for a particular organization, you need to identify

the kinds of operating scopes that exist and the

properties for them. It is very difficult to generalize about operating scopes

in the abstract, but location is a common factor.

The sub-types of operating scope may form an inheritance hierarchy of their own

if there are many of them. In particularly complex cases

you might see an operating scope type placed on the knowledge level to show

which accountability types can have which operating scope types.

(In this case the instances of operating scope type must match the sub-types of

operating scope. Operating scope type

is thus a power type of operating scope.)

9. Post

Often the operating scopes of a person—their responsibilities, including many of

their accountabilities - are defined in advance as that

person's job description. When a person leaves a job, the replacement may

inherit a full set of responsibilities.

These responsibilities are tied to the job rather than the person.

We can deal with this situation by introducing the post as a third sub-type of

party, as shown in Figure 15. Any responsibilities that are

constant to the job, whoever occupies it, are attached to the post. A person

fills a post by having an accountability to the post.

The notion is that a person is responsible for the responsibilities of the post

for the period of time that they are appointed to the post.

Example: Paul Smith is the head of the high-volume product development

team. We can describe this by having a post for the head of the

high-volume product development team. This has a management accountability with

the high-volume product development team (a party).

Paul Smith has a separate accountability (of type appointment) to this post.

Example: The transplant surgeon post at a hospital has in its job

description the requirement to do 50 renal and 20 liver transplants in a year.

This post has an accountability with the hospital and protocol scopes for 50

renal transplants and 20 liver transplants.

Figure 15 Post.

Posts are used when accountabilities and scopes are defined by the post and do

not change when the holder of the post changes.

Appointments to posts are accountabilities.

Posts should not be used all the time. They add significant complexity to the

operational level with their extra level of indirection.

Only use posts when there are significant

responsibilities that are static in a post and people change between posts

reasonably often.

Posts are not necessary in models in which all responsibilities can be attached

to a person.

|