|

Using the Accounting Models

To fully understand this section, you will

need to read

Analysis of Accounting first.

This page shows how we can use the patterns presented in

Analysis

of Accounting. This is a

difficult task because the accounting patterns in

Analysis

of Accounting

are quite abstract.

To

understand how the patterns really work, we need to look at a fully worked

example.

This section looks at accounts and posting rules used in a model for a

telephone utility, Total Telecommunications (TT). In the best textbook

tradition,

the examples presented here are somewhat simplistic. They should be sufficient

to at least give you a feel for how the models work. The aim is to illustrate

the

use of the account model, not to model a telephone company.

TT's basic billing plan is very simple. All calls are divided into day and

evening calls. Daytime runs from 7:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. The classification is

based

on the time the call begins.

Day calls cost 98 cents for the first minute and

30 cents for subsequent minutes. Evening calls cost 70 cents for the first

minute, 20 cents

for

the next 20 minutes,

and 12 cents thereafter. The government charges a 6 percent tax

on the first $50 of calls in a calendar month and 4 percent on calls thereafter.

For the sake of simplicity, we have skipped the case of calls crossing the

boundary.

We with a discussion of the Structural Models (Section 1), which

is naturally based on the patterns presented in

Analysis

of Accounting.

We then look at some

interesting features of implementing the Structure (Section 2). To set up the objects,

we begin by setting up New Phone Services (Section 3),

followed by setting up Calls

(Section 4). We then take a first look at the posting rules, examining the code for

implementing Account-based Firing (Section 5).

Three example posting rules are given: Separating Calls into day and evening

(Section 6), Charging for Time (Section 7), and Calculating the

Tax (Section 8).

Each rule illustrates a particular aspect of

behavior.

The first two rules operate on an entry-by-entry basis, and a common

super-type - each entry posting rule - handles the common behavior. Splitting

charges into day

and evening is handled by a simple singleton sub-type of each

entry posting rule. A different scale is required for day and evening calls, but

since the basic process

is the same, we can use a strategy object parameterized

by a rate table. This allows us to handle any posting rule that charged

according

to some scale based on the

length of the call. The rate table class used as the

strategy object can be used for any calculation based on lengths in this way.

Indeed it is used for the next posting rule

that calculates tax. Unlike the

prior

rules, this rule has to work on a month-by-month basis, but we cannot assume

it is run once per month.

The three posting rule classes should give a good idea of how we can use

the account/inventory patterns to show both monetary and non-monetary

transactions.

In developing code we like to begin with building the skeleton of the structural

model. We then prototype, being careful to update the structural model as we go

(otherwise, we can forget where we am). As tricky behaviors come up, we may use

event diagrams or interaction diagrams at the start or during the programming.

If

we think it is important to document what we have done with these behaviors (as

we

do for this book), we produce diagrams once we have the code sorted out. The

diagrams are not replacements for the code; they help to illustrate what the

code

is doing. (With a suitable tool, however, event diagrams could be used as the

code.)

1. Structural Models

The best place to start is with the structural models because they give an

overview of the various pieces of the final model. Figure 1 shows the packages

within the model. I've split the model into two packages: phone service and

account. One virtue of an accounting framework is that it can be used for

different industries, so we need to ensure that the accounting model is kept

separate from (that is, has no visibility to) any industry-specific concepts.

Figure 1. The packages for the TT example.

The account package holds the abstract accounting types, which are extended by

the

phone service package for this specific domain.

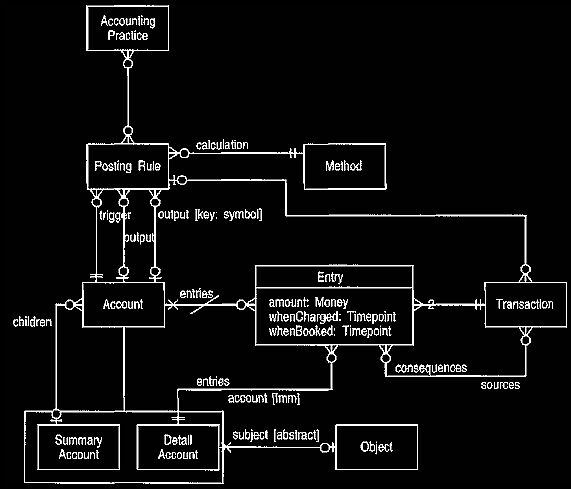

Figure 2 shows the accounting model for TT, based on the patterns from

Analysis

of Accounting.

This model has three associations from posting rule to account.

Trigger and output are familiar, but the keyed output is new. This allows

multiple

output accounts for those posting rules that need them. The need will become

clear with examples later in the section.

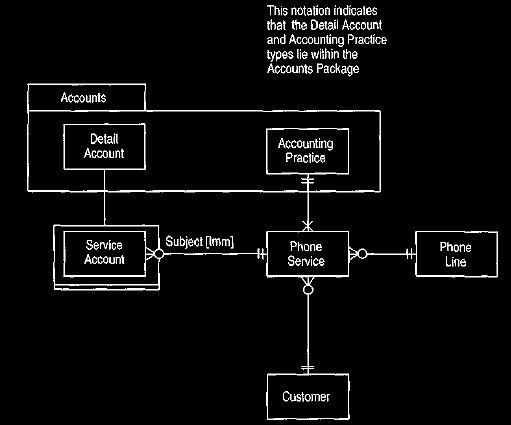

Figure 3 shows the model of the phone service. Customers are allowed

multiple phone lines. A phone service is really a phone line assigned to a

customer. Each phone service is tied to an accounting practice that describes

how it will be billed. This diagram illustrates why the subject mapping was

added to detail account shown in Figure 2. We need a way to find out what

detail account is accounting for, but we do not want visibility from the account

package into the phone service package because it would compromise reuse.

Thus we form a sub-type of detail account. With sub-typing, visibility only runs

from the sub-type to the super-type. It is perfectly permissible for the service

account to know the phone service because they are both in the phone service

package. However, we could have reference to a detail account and not know it

is a service account. The abstract mapping on detail account tells us that a

detail

account could be linked to an object (type unspecified) as a subject. This will

all

be implemented by sub-types of detail account - a classic case of polymorphism.

Figure 3. The structural model of phone service.

2. Implementing the Structure

This model has no account types. The posting rules are defined by summary

accounts. For the examples in this section, we could use either account types or

summary accounts to define posting rules. Using summary accounts is slightly

more complicated, making it a better illustration. The high-level summary

accounts that are defined are held in a class variable in the account class and

are accessible with the class method findWithName: aString.

Various bits of code need to find a service account for a particular phone

service under a particular summary account. It's not difficult to think up

various

ways of doing it: asking a phone service to find the account under a given

summary account or asking a summary account to find its descendent

attached to a phone service. Both of those ways are reasonable, but it is

difficult

to choose which one is the best. Furthermore, each implies a certain navigation

path, and one may be better than the other. In such cases we can use an entirely

different technique, building a class method. Then we

can implement the method

with either path and change the method without

changing the declarative interface. It also makes it easier to remember where

these find methods are.

In practice a method on phone service, such as accountNamed: aString, is

often more convenient to use. That method calls findWithPhoneService:

topParent and provides the advantages of both approaches.

All we use two-legged transactions, although the model

supports multilegged transactions. We can create a two-legged transaction with

the special creation

methods for transaction. One method

carries all the information, including the source entries and the creation

posting

rule. The other method is used for the

initial attributes read in at the

beginning.

There is a number of coding techniques. A constructor parameter

method (prefixed with set) initializes the new object with parameters.

Within the creation parameter method, precondition checking is done. To improve

performance, the checking can be removed.

Another element from design by contract is

the use of an invariant check.

3. Setting Up New Phone Services

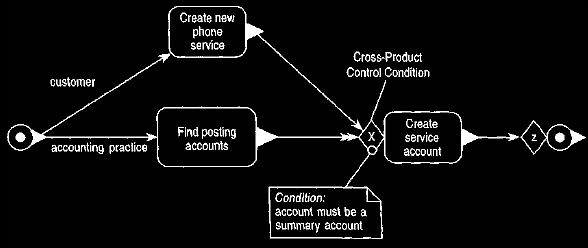

Creating a new phone service is not simply a question of instantiating a phone

service object. Service accounts must also be created to get the accounting

system going. Although this example does not contain more than one accounting

practice, it should be flexible enough to set up the accounts for whichever

accounting practice is being used, as shown in Figures 4 and 5.

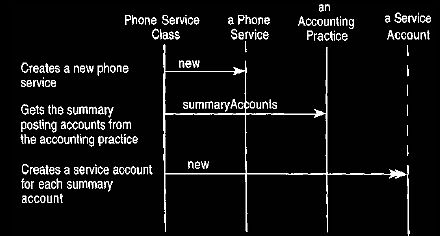

Figure 4. Event diagram for creating a new phone service.

This diagram uses a cross-product control condition (an extension to the regular

event diagrams). The control condition is evaluated for each combination of its

incoming triggers, in this case for each combination of new phone service and

posting account. It invokes the create service account operation for each phone

service and summary posting account in the accounting practice.

Figure 5. Interaction diagram for creating a new phone service.

To determine which accounts are required, the accounting practice is asked

for its posting accounts, as shown in Figure 6. An accounting

practice can contain posting rules that reference detail accounts (although that

it

is not done here). Thus the posting accounts have to be filtered to keep only

the

summary accounts.

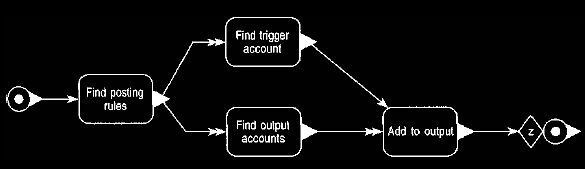

Figure 6. Finding posting accounts.

We want the trigger account for each posting rule and all the output accounts

for

each posting rule.

4. Setting Up Calls

Phone calls are modeled as transactions from a network account to a basic time

account. The units for phone call entries are minutes.

The method setting up of a phone service and the

placement of some sample calls can be denned on a class called Scenario: methods can get quite complex;

thus it is good

practice to put them on a scenario object (using scenario in the

sense of a use-case, not as defined in

Analysis of Trading, Section 4)

to keep them under control

if

no proper testing framework is available. The variables basicAccount and

theService are class variables of this class.

Using user-defined fundamental classes, such as quantity, can make creating

new objects difficult. Hence quantity has a method n: aString, which creates

a new quantity from the string. This is a personal convention that we use since

fromString: aString can get rather unwieldy.

5. Implementing Account-based Firing

We use the account-based triggering scheme here (see

Analysis of

Accounting, Section 3). Each

account has a method to process itself by firing

all posting rules that use it

as a trigger.

Entries are held in orderedCollection, with new ones added on the end. The

TaskProcessed instance variable keeps track of the state of processing.

6. Separating Calls into Day and Evening

To separate the calls into day and evening calls, we look at each entry,

consider

the time on the entry, and then make a transaction from the basic time

account

into either the day time account or the evening time account.

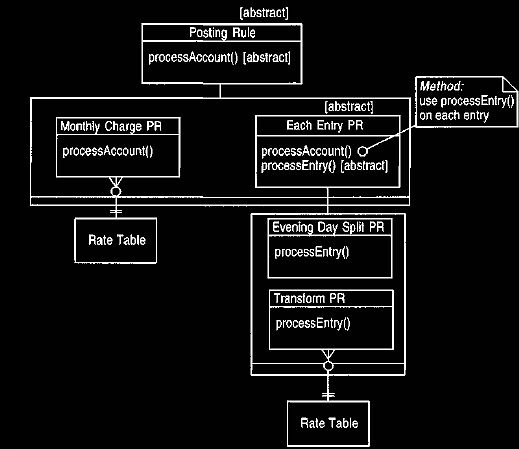

A posting rule that operates on an entry-by-entry basis is quite common. We

can create an abstract sub-type of posting rule called an each-entry posting rule

(the class EachEntryPR). This sub-type calls the operation process Entry:

anEntry on each unprocessed entry in the triggering account, as shown in

Figure 7 and Listing 8.

The message currentInput: loads an instance variable to hold the service account

that is being processed by the posting rule. It

is

accessed by private methods

and is only defined within the execution of

processAccount.

Figure 7. Each-entry posting rule's method for processing an account.

We use the process entry operation on each unprocessed entry.

A temporary, private instance variable is often

used in such cases because posting rules in general (although not in this case)

are

defined as instances.

Thus we cannot instantiate them for invocation of the

rule. An alternative is to treat the defined posting rule instance as a

Prototype

and

clone it for execution.

The currentInput: message also sets up current output service accounts

for the same phone service as the one provided as input.

This method does not do the actual calculation and posting. Instead it is

done by processEntry:, which is abstract and should be defined by subclasses.

Thus we see three layers of subclassing here. PostingRule defines the basic

interface and services of posting rules. The process account method on

EachEntryPR is a template method,2 which outlines the steps of processing an

account entry by entry but leaves a subclass to actually work out how to process

each entry.

For this posting rule we can define new subclass of EachEntryPR called

EveningDaySplitPR. This is an example of the singleton class implementation

(see

Analysis of Accounting, Section 6.1). Hard-coded into this class are the appropriate accounts,

which are set up at initialization.

The splitting is done by the overriding processEntry: method, as shown in

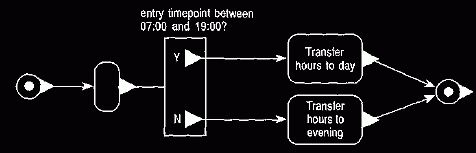

Figure 8.

7. Charging for Time

Charging for both the evening and day calls follows the same pattern, as shown

in

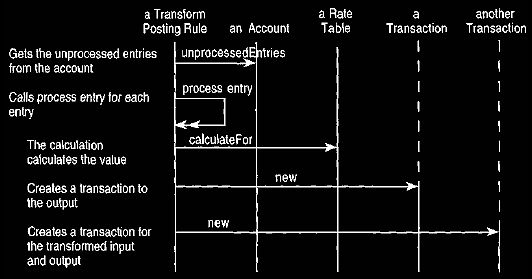

Figure 9. Again the charges are calculated on an entry-by-entry basis,

so a

subclass of EachEntryPR is used. Two posting rules are used—one for day, one for

evening. The same class, TransformPR, is used for both of them.

A template method is a skeleton of an algorithm that defers some steps to

subclasses.

Figure 8. Evening/day split process rule's method for the process entry

operation.

Figure 9. Interaction diagram for processing an account with a transform

posting rule.

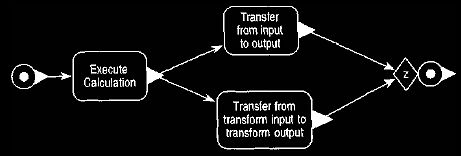

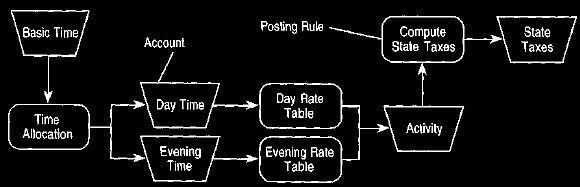

A special feature of this posting rule is that it is triggered by an entry in

minutes but produces entries in dollars, hence the term transform. Its actual

reaction is to generate two transactions. One transfers the minutes back to the

network account, thus completing the cycle for minutes. The second generates a

new transaction in the money world: from a network income account to an

activity account, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10. Event diagram for transform posting rule's method for the process

entry operation.

The transformedAmount is calculated by a method object (see

Analysis of

Accounting, Section 6.2),

specifically a rate table. The method

class defines

the abstract calculateFor: method. The rate table is a subclass

that stores a two-column table of quantities to produce the kind of graded

charging that

the problem demands. It is implemented using a dictionary. The

keys of the dictionary indicate the various threshold points, and

the corresponding value

indicates the rate that applies up to that threshold. The top rate indicates which

rate applies once you get over the top threshold.

A pseudo-method can show the rate table then calculates the amount. It does this

in two parts: taking each step in the rate table and adding any amount

over the

top threshold. There is not much point showing a diagram for this; the tables

indicate what is needed from a conceptual perspective clearly enough.

One

particular thing to watch for with these systems is that they can handle both

positive and negative numbers the same by using absolute values.

8. Calculating the Tax

The final posting rule shows the calculation of the tax. This rule differs from

the previous rules in that it does not operate on an entry-by-entry basis. This

posting rule has to look at all charges over a one-month period to assess the

tax.

Another complication is that we cannot (or rather do not wish to) guarantee

that the posting rule is only run once at the end of the month. Thus the posting

should take into account any tax already charged for the month due to an

earlier firing. This follows the principle that the posting rules should be

defined

independently of how they are fired. This increases flexibility and

reduces coupling in the model.

The MonthlyChargePR class is a sub-type of posting rule and thus implements

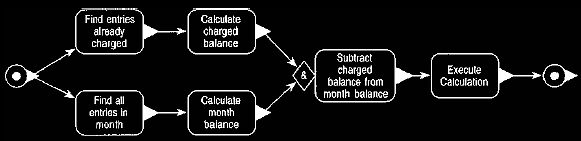

processAccount, as shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11. Monthly charge posting rule's method for processing an account.

This process is based on a balance over a time period, rather than each entry.

Each month is processed with processForMonth:, as shown in Figure 12.

The final transaction is from the output account to the input account,

because the activity account will be increased due to the tax liability.

Figure 12. Event diagram for processing a month.

9. Concluding Thoughts

This is a very simple example, so it is difficult to draw too many conclusions

from it. The reader can convincingly argue that this problem can be

tackled in a

much simpler form without all this framework stuff. The framework, however, is

valuable for scalability. A real business may have dozens

of practices,

each with dozens of process rules. With this structure we represent a new

billing plan by an accounting practice. When we build a new practice,

we create

a network of new instances of the posting rule. We can do this without any

recompilation or rebuilding of the system, while it is still up and running.

There

will be unavoidable occasions when we need a new sub-type of posting rule, but

these will be rare.

9.1 The Structure of the Posting Rules

Figure 13 shows the generalization structure of the posting rules discussed here. The abstract posting rule class has an abstract processAccount

method.

The sub-types each implement processAccount. The each entry posting

rule implements this method by calling another abstract method, processEntry,

on each entry. The further sub-types implement processEntry as needed. The

day/evening split posting rule's method is hard coded, while the transform

posting rule delegates to a rate table.

Figure 13. Generalization structure of posting rules

The example shows how acombination of abstract methods, polymorphism, and delegation can provide

the kind of structure that supports a variety of posting rules in an organized

structure.

This is not the only structure of posting rules we could use. Another

alternative would be to combine the two steps of working out the charge into a

single step. Such a posting rule would have two rate tables, one for day

charges and one for evening charges, and would be responsible for both the

splitting and the rate table charging.

There are no rules for deciding how to divide up posting rules. Our fundamental aim is to be able to build new practices without needing a new

sub-type of posting rule. We want to have as small a set of sub-types of posting

rule as we can, for that will make it easier to understand and maintain the

posting rule types. Yet we need these sub-types to have all the function that is

required so we can put them together for new practices. We want to minimize

the times when we need to build new posting rule sub-types.

Simpler posting rules result in larger practices and are usually more

widely available. We tend to keep posting rules to small behaviors initially. If

we see a frequently used combination of posting rules, then we might build a more

functional posting rule to represent that combination.

9.2 When Not to Use the Framework

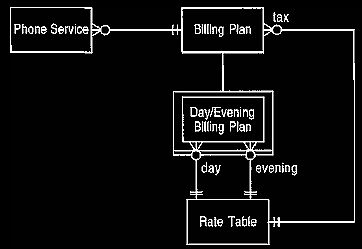

An alternative to using this framework is to have only one class per billing

plan

to handle all the behavior (day/evening split, charging, and taxing), as shown

in Figure 14. The class would take all the entries in a month and produce a bill.

There would be one such object for each billing plan.

Figure 14 Using a billing plan.

A billing plan is simple but not as flexible.

This approach is quite plausible. Although there may be many billing plans,

there are usually a few basic methods for billing that can be parameterized,

much

as the transform posting rule can be parameterized for many different rate

schedules. Such a type, for this problem, would be parameterized by an evening

rate table, a day rate table, and a taxing rate table.

The key question is how many sub-types of billing plan there are. If we

can represent all the billing structures with a dozen or so sub-types of billing

plan (although there might be hundreds of instances), then using a billing

plan type is plausible. The accounting model's strength is that it allows you to build the equivalent of new sub-types of billing plan by wiring together

posting rule and account objects. This is a powerful advantage if there is a

large or frequently changing set of sub-types of billing plan.

Another way to think about it is to consider the billing plan as a posting rule that posts from the basic time account to the activity account in one step.

Using

accounts would still be valuable to give the history of phone calls and

charges

at

the input and result of billing plan. We would lose the intermediate totals.

9.3 Accounting Practice Diagrams

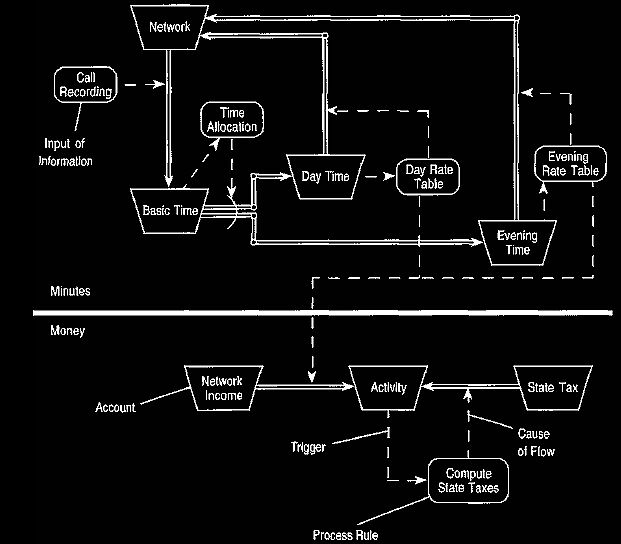

A diagram often helps to visualize a complex problem. Figures 15 and 16 are

suggestions (and most certainly tentative ones) in that direction. Complex

practices will be helped by these kinds of diagrams. We might imagine that we

could build a system by drawing a diagram and decreasing the amount of

programming required and thus increase the productivity of such applications.

Practice should result in a diagram form that is simple yet conveys the key

information. Figure 15 has the advantage of being simple, displaying the key

triggering and output relationships. It does not, however, show the full flow of

accounted items in the way that Figure 16 does. If you use these

Figure 15. A simple way of diagramming the layout of process rules and

accounts.

It shows the trigger and main output account for each posting rule but hides the

full

flow of transactions.

Figure 16. A more expressive diagram of the accounts and posting rules.

This diagram makes the flow of transactions explicit. Each posting rule is

triggered by a

single account and causes a number of flows.

The direction of the flow shows

where

items are withdrawn and deposited. The diagram shows more information and is

thus

more complicated.

patterns, we strongly recommend using diagrams. Start with the ones suggested

here and let the diagram standard evolve to one that is the

most useful (and let

us know what it is).

Back to Analysis of Accounting

|